It was not until a few weeks ago that I came across an idea for recreating a performance which resonates with some of the discussions we have been having on the module. I knew I wanted to address some of the ideas that came up in our lesson with Daniel Hunt, in which we talked about mediatised, digital performances, audiences existing on virtual levels and the idea of the Posthuman.

Then, in the lead up to remembrance Sunday this November, I was also looking for ways to raise money for the British Legion. This was when I came across Vodafone’s Big Poppy Run. “Inspired by the thought of wounded soldiers like himself and those who never made it home, young former Royal Marine Ben McBean ran 31 miles across London in the shape of a huge poppy, guided by a smartphone on the Vodafone network” (The Royal British Legion, 2014).

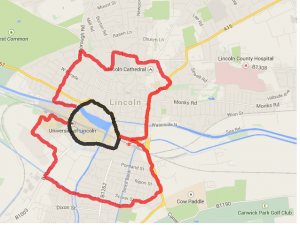

So, in response to what McBean carried out in London, I have begun to do the same in Lincoln. Today I have finished running the parameter of my poppy around Lincoln town centre, colouring in the streets on the map as I go.

Between now and the show back to my peers on December 2nd (This date changed – the performance will now take place January 20th) I intend to run every street left inside the poppy parameter above. You me be wondering where exactly this ties together with the theoretical work we have been studying.

My main intention for this performance is to examine the layers of performance which exist for what I am calling The Lincoln Red Poppy Run. I define performance in this context as any point where someone is a spectator to someone contributing to this project. So for example so far I have established the following layers of performance:

The Immediate – Those in studio x who will be watching both me presenting the performance, and to the volunteer who will be running the last stretch of the poppy (visible from the window).

The Virtual – For the purposes of the demonstration, my volunteer will be linked up to us in the studio via Skype so that we have direct, digital contact with him. Also as he runs, we will be able to follow his progress, meaning we can complete the poppy image.

The Unknowing – Those “audience members” out in the street who will be passing the runner, unaware of the fact they are part of a performance.

The Performer Himself – He will be able to see us in the studio via the Skype uplink, so he will be the spectator to us observing him.

So far it is these different aspects that I am exploring to establish how a performance can have multiple layers (with mediatised assistance). This was an idea that has developed from our class work on the Lincoln Noir project which you can read about on a previous blog post.

This project is also inspired by the works of Blast Theory, and in particular their project Can You See Me Now? This involved a game of tag to be played online and in real life simultaneously. One team play at a computer, whilst the second team take to the streets; “tracked by satellites, Blast Theory’s runners appear online next to your player on a map of the city. On the streets, handheld computers showing the positions of online players guide the runners in tracking you down” (Adams, 2001). The game allows up to a hundred people to play the game, this extending the layers of performance, from just the physical and digital, to also include the social world as players are encouraged to co-ordinate and share tactics. The game creates a hybrid canvas for performance in which those involved can explore both realms of possibility. It is this overlapping which Blast Theory feels is at the core of what they achieved with Can You See Me Now? “In what ways can we talk about intimacy in the electronic realm? . . . Against this backdrop can we establish a more subtle understanding of the nuances of online relationships” (Adams, 2001). Entering into the Posthuman age, when the greater amount of the average person’s social interaction is conducted over the internet, Can You See Me Now? explores this field. It brings players and runners into the same virtual space from all around the globe and introduces physical social interaction into the virtual world.

Works Cited

Adams, Matt (2001) Can You See Me Now?, Blast Theory [online] Available at: http://www.blasttheory.co.uk/projects/can-you-see-me-now, Accessed [21/11/2014].

The Royal British Legion (2014) ‘The Big Poppy Run – Vodafone Firsts’, BritishLegion.org [online] Available at: http://www.britishlegion.org.uk/about-us/calendar-of-events/fundraising/the-big-poppy-run-vodafone-firsts, Accessed [21/11/2014].

Vodaphone Firsts (2014) ‘The trailer – Ben McBean’s #First Big Poppy Run PR’, YouTube [online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ro40EU0I0L8#t=13, Accessed [21/11/2014].