This week we studied the importance of researching historical context, and in particular Marvin Carlson’s notion of ghosting. All performances can be seen as historical events, they hold a certain resonance to the past. The theatre “is always at vanishing point” (Blau, 1982, p. 28) and “becomes itself through disappearance” (Phelan, 1993, p. 146). A concept with similar qualities to one shared during our observations into scenography (previously in the module) as the stage being an ephemeral void.

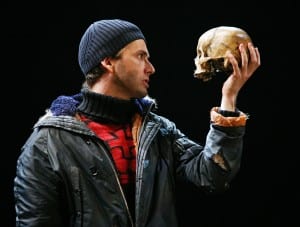

No theatrical event can occur without being influenced in some way by what has previously occurred in some context. It is by responding to what has come before that informs what comes next. Even with regard to performance, “every performance . . . embeds features of previous performances” (Diamond, 1996, p. 1); something presented on the stage has reference to a past event. This is the basis for Carlson’s idea of ghosting and the stage as a haunted space. “Everything in the theatre, the bodies, the materials utilized, the language, the space itself, is now and has always been haunted” (Carlson, 2001, p. 15). For example let’s look at a popular piece of recent theatre; the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2008 production of Hamlet starring David Tennant as the Prince of Denmark. First performed at The Courtyard, Stratford-upon-Avon, the extent to which we can examine the different variations of ghosting involved is near infinite. Firstly, as Carlson explains, the space itself is a grounds for which haunting happens. When choosing to perform Hamlet in Stratford-upon-Avon for instance, the birthplace of William Shakespeare, the production is haunted by the playwright himself. Then there is the stage, The Courtyard, which will also be haunted by its previous productions, previous audiences and pretty much anything or anyone to have inhabited that particular space over time.

After the actual space we can begin to look at variations of ghosting within the performance. Turning our attention to the protagonist; when most think of David Tennant in 2008, the immediate though would be his role as the Doctor in Doctor Who. “Tennant . . . has no difficulty in making the transition from the BBC’s Time Lord to a man who could be bounded in a nutshell and count himself a king of infinite space” (Billington, 2008). Audiences will naturally be intrigued to see Tennant’s transition from Doctor Who to Hamlet and will watch his performance comparing him to his well known TV character. This meaning that Tennant’s performance is haunted by his previous work, when audiences will not only be comparing his depiction of Hamlet to other famous actors who have taken on the challenge (Laurence Olivier to name but one), but to his previous characters from different productions.

This is less than a percentage of the amount of ghosting that occurs in one production, as Carlson lists also include, the director’s previous works, the staging, the appearances props and costumes have had in other works of art. These are but some of the other aspects to consider in what is arguably a never-ending list of hauntings.

So we were asked the question: Why? Why do theatre historiography?

The responses we collated as a class resembled something as never-ending as the list of ways in which theatre can be haunted.

Among the responses, understanding what the original performance conditions consisted of was perhaps the best reason, in my opinion, to examine the ghosts of theatre’s past. I favour this reason because I believe that any director (or producer / dramaturg for that matter), before he or she makes any attempt at reviving a performance, needs to understand the decisions made for the first production, and any/all subsequent productions that followed. They need to make themselves aware of the cultural, political and aesthetic impact of the original theatrical event.

Works Cited:

Billington, Michael (2008) ‘Hamlet’, The Guardian [online] Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2008/aug/06/theatre.rsc, Accessed [21/11/2014].

Blau, Herbert (1982) Take Up the Bodies: Theatre at the Vanishing Point, Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

Carlson, Marvin (2001) The Haunted Stage: The Theatre as Memory Machine, Ann Arbour: University of Michigan Press.

Diamond, Elin (1997) Unmaking Mimesis: Essays on Feminism and Theatre, New York: Routledge.

Phelan, Peggy (1993) Unmarked: the Politics of Performance, London: Routledge.